Yes, you read it write, This article is about the Apple that didn’t fall.

We all have heard the tale of how an apple fast-paced the course of our understanding to the fundamental forces of the universe by just falling on to the head of a free-minded human. But now let’s see the other side of the story where the apple didn’t fall ever.

Picking up from the where we left talking about the unlucky painter and the happiest though of Einstein’s life, we extended that to a thought experiment where the apple was thrown with superhuman strength which kept “falling” and not “floating” around Earth. This falling thing is not random and is carefully governed (or approximated?) by the gravitational forces and some certain velocities that create orbits.

Well what are they you may ask? They are nothing but infinite possible paths around our Earth. What does an object do when on this path? Well pretty much revolve the earth while “trying” to fall. That’s it, that is an orbit. But have we categorized them? Yes, we have! With this let’s go head first into the science of Earth’s orbital zones, namely, Low Earth Orbit (LEO), Medium Earth Orbit (MEO), and Geostationary Orbit (GEO).

The Orbital Playground.

Before starting, imagine this: you’re standing atop the tallest mountain, throwing apples into space at different speeds. Each speed represents a particular orbital zone. Now we are ready!

LEO: Low Earth Orbit.

If your apple travels at a speed between 7.8 km/s and 8 km/s, it enters a Low Earth Orbit (LEO). This is the zone closest to Earth, ranging from 160 km to 2,000 km above the surface.

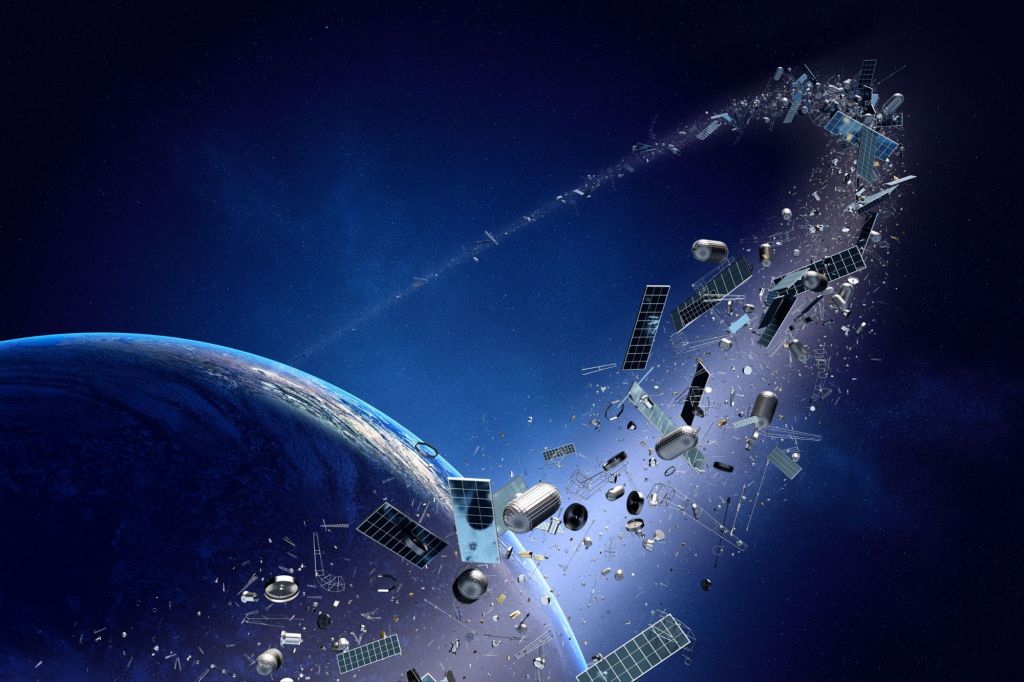

LEO is like the happening downtown of space, crowded and busy. Most satellites, the International Space Station (ISS), and even space junk revolve here. The proximity to Earth makes LEO perfect for high-resolution imaging, weather monitoring, and communication systems. But what is so special about LEO?

- Satellites in LEO are closer to Earth, which means shorter travel times for signals.

- This orbit is ideal for Earth observation missions, like tracking hurricanes or spying on military activity.

- It’s also the earliest to reach—making it perfect for human space missions like the ISS.

But there’s a catch: objects in LEO experience drag from Earth’s upper atmosphere, requiring frequent adjustments to maintain their orbits, aka. orbital correction maneuvers.

MEO: Medium Earth Orbit.

To reach Medium Earth Orbit (MEO), the apple would need to be thrown faster—typically 3.9 km/s to 5.4 km/s, relative to the surface, and launched to altitudes of 2,000 km to 35,786 km.

MEO is home to navigation satellites like GPS, GLONASS, and Galileo. Satellites in this orbit take around 12 hours to complete one revolution around Earth, striking a balance between coverage and latency.

MEO satellites cover larger regions than those in LEO. And they are ideal for navigation and positioning systems, like the GPS in your phone. Unlike LEO, objects in MEO experience far less atmospheric drag, which makes this orbit relatively stable for long-term missions.

GEO: Geostationary Orbit.

Now, let’s take the apple to 35,786 km above Earth (and how did you calculate this?). At this altitude, a satellite’s orbital speed matches the Earth’s rotation speed, keeping it “stationary” over a fixed point on the equator.

What makes GEO special? Well, since it is always above you, it can always see you, send you data continuously without making a swarm of other satellites like the Starlink Network. Monitoring weather is the easiest task one should be able to think. TV broadcasting and communication networks are other primary objective a satellite stationed at GEO is tasked with. A satellite here takes 24 hours to complete one orbit, matching Earth’s rotational period.

Orbits and Everyday Life.

These orbital zones might seem distant, but they directly impact our lives:

- LEO: Enables global internet coverage, like Starlink.

- MEO: Keeps planes and ships on course through GPS.

- GEO: Streams your favorite shows and monitors cyclones.

Without these orbits, modern communication, navigation, and weather prediction would easily crumble.

A Personal Note: Why It Matters

When I think about the apple we threw into space, I wonder how such simple physics—Newton’s laws of motion trying to capture the beauty of gravitation field—governs complex systems like satellites and space stations. Understanding orbits doesn’t just connect us to the cosmos; it also shows us how interconnected our technology and daily lives are with the universe above.

“The important thing is not to stop questioning.”

by Albert Einstein

So, next time you watch a weather report or navigate with GPS, remember: Surely it all didn’t began with someone throwing an imaginary apple into space but that someone, who is me, might be doing it so, right this moment.

Until next time, keep looking up, and maybe—just maybe—you’ll spot a satellite gliding gracefully through its orbit.

TL;DR.

Generated using AI.

- Orbit Basics: Instead of falling, an apple thrown fast enough enters orbit, “falling” around Earth due to gravity and velocity.

- Orbital Zones:

- LEO (160–2,000 km): Close to Earth, crowded with satellites like ISS and Starlink, but needs adjustments due to drag.

- MEO (2,000–35,786 km): Stable orbit for GPS and navigation systems.

- GEO (35,786 km): Matches Earth’s rotation for constant communication and weather monitoring.

- Why It Matters:

Orbits power navigation, communication, and weather prediction, showing how physics connects us to the cosmos.

Leave a comment