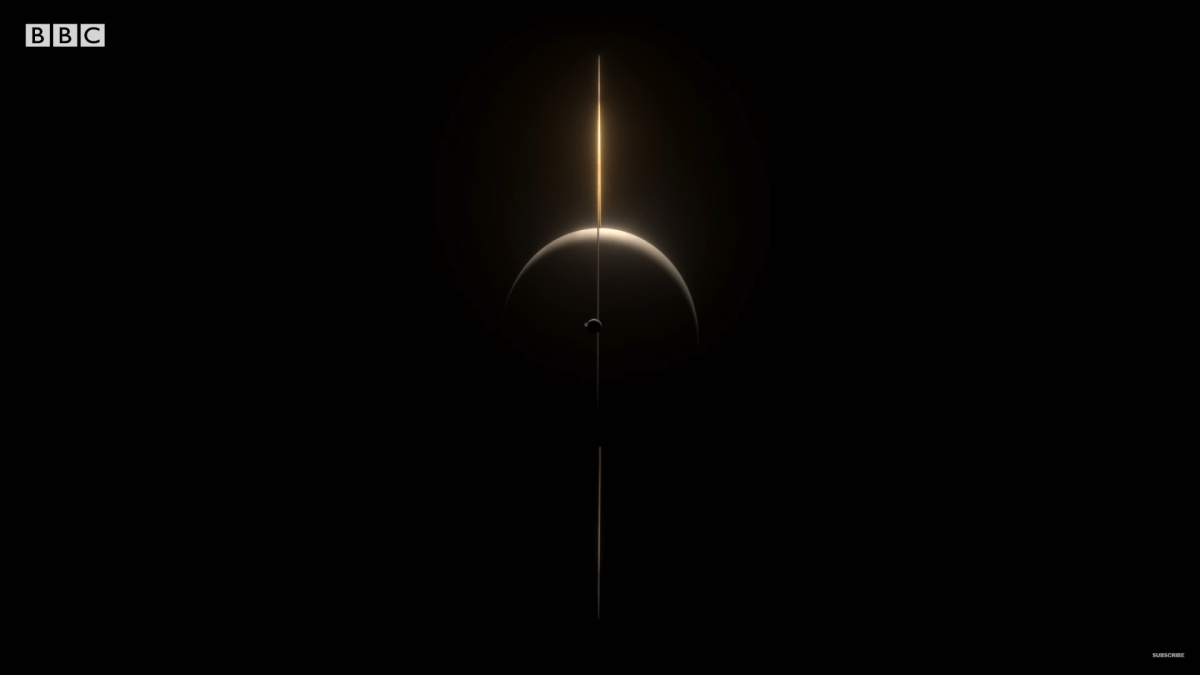

I am keeping my promise from last time of going in depth about the mathematics and physics involved in tearing the satellites apart and form beautiful ring systems around Saturn and alike planets. We also learnt that at some point, gravitational forces can tear orbiting bodies apart. But how does this actually work, and why does it happen so consistently around massive planets? With this context, I present to you, the Roche Limit!

Tidal Forces and Gravitational Stresses.

Before we define the Roche limit, we need to understand the nature of tidal forces. Imagine a small moon orbiting a giant planet. The side of the moon that is closest to the planet experiences a slightly stronger gravitational pull than the side facing away. This difference in gravitational pull is what we call a tidal force. Just as Earth’s oceans rise and fall due to the Moon’s gravitational pull, a small moon orbiting a large planet is stretched and squeezed by these tidal forces.

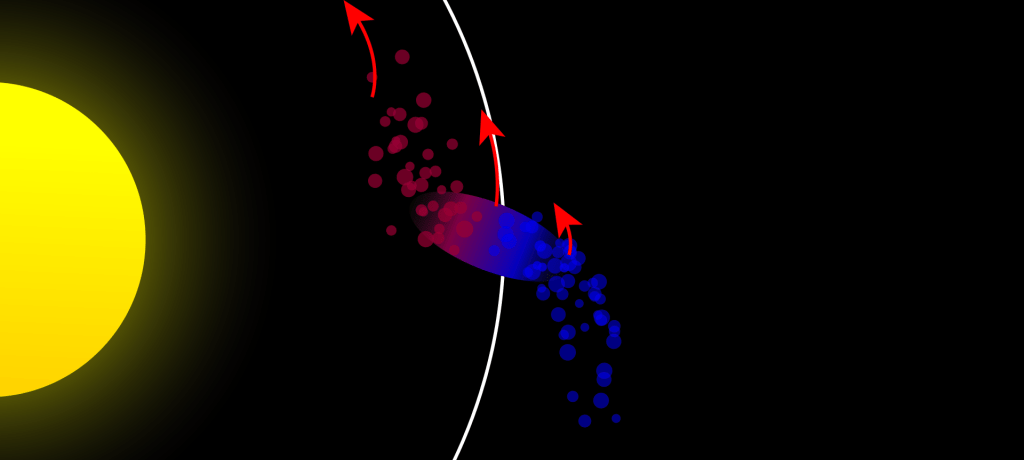

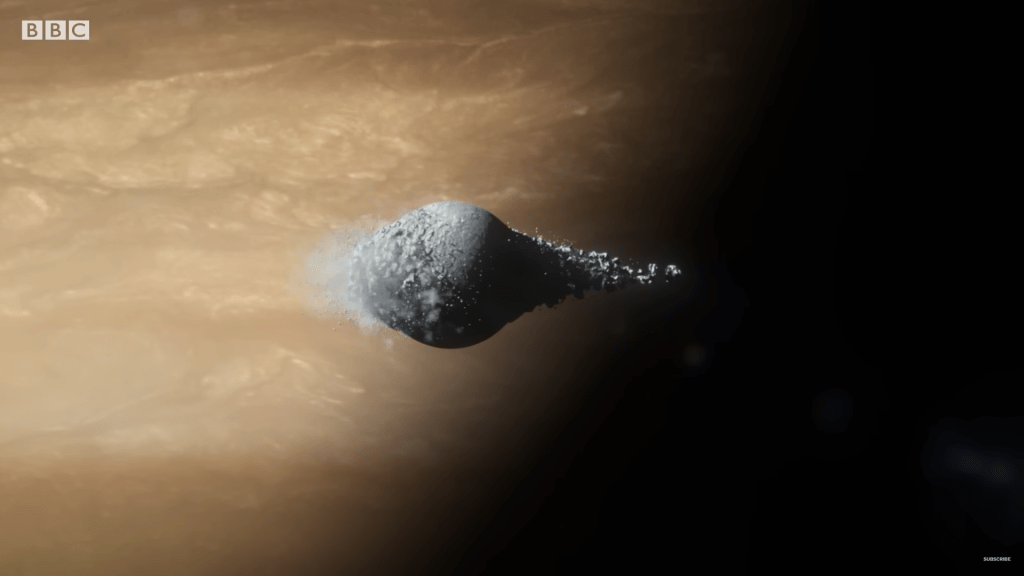

If the moon is far enough away, its internal gravitational strength is sufficient to keep it together. However, as it moves closer to the planet, the differential gravitational force acting upon it increase. It can become so intense that they exceed the moon’s own gravity—the force that normally holds it together as a cohesive object. When that happens, at this stage, moon can not hold its outer layer within it self, and the moon starts to disintegrate, and what remains is a field of scattered debris orbiting the planet. Over time, this debris may arrange itself into a beautiful ring, like we see in case of Saturn.

What is Roche Limit?

The Roche limit is the theoretical radius within which a celestial body, held together only by its own gravity, will start to disintegrate due to the tidal forces exerted by the planet it orbits. In simpler terms, if a moon ventures too close to its parent planet—crossing inside this critical boundary—it will be pulled apart.

This phenomenon is not just about destruction. While it may sound grim that a moon could be ripped into fragments, nature sometimes uses these disruptions to create new wonders. In fact, Saturn’s spectacular rings likely formed from such events. Either an icy moon wandered too close and broke apart, or the building blocks of a moon were pulled into this zone before they could fully come together.

Think of the Roche limit as the place where two opposing forces reach a tipping point. On one side is the gravitational force that holds the moon’s material together; on the other side are the planet’s tidal forces trying to tear it apart. A stable moon depends on the delicate balance between these opposing influences.

When outside the Roche limit, the moon remains intact. Although tidal forces exist, they are too weak to overcome the moon’s internal cohesion. As the moon moves closer, tidal forces strengthen rapidly. If it crosses the Roche limit, these tidal stresses surpass the moon’s self-gravity, leading to catastrophic breakup.

Let’s derive it.

A full, detailed derivation involves advanced gravitational analysis, but we can sketch the reasoning:

Balance of Forces:

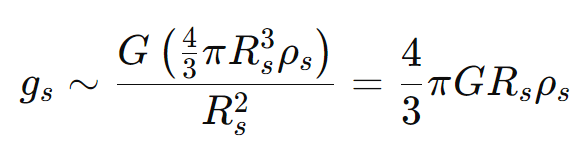

Imagine a small mass element on the surface of the satellite. This mass is held in place by the satellite’s own gravity (which tries to pull it inward) and is simultaneously pulled outward by the tidal forces of the planet. The inwards gravitational force on the satellite is given by,

Tidal Force Approximation:

Tidal force is roughly the difference in the planet’s gravitational attraction across the diameter of the satellite. If the satellite’s radius is ‘Rs’, and it orbits at a distance ‘d’ from the planet’s center, the tidal acceleration on its near side is a bit stronger than on its far side. The tidal force, which is differential gravitational force on the satellite by planet is given by,

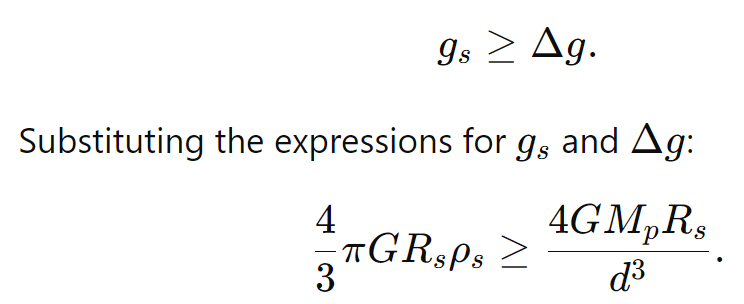

Condition for Disruption:

For the satellite to remain intact, its self-gravity must exceed the tidal force that tries to pull it apart. If we treat the satellite as a fluid sphere of density ρs, its own gravitational acceleration (holding it together) is proportional to ρsRs. The tidal force from the planet depends on the planet’s mass Mp (or equivalently density ρp and radius Rp) and the distance ‘d’.

Arriving at the Formula:

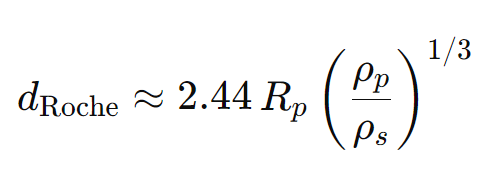

By equating the tidal force to the satellite’s self-gravity, one derives a relationship that sets a critical orbital radius dRoche. After some algebra and assuming the satellite is fluid, this process yields the commonly used Roche limit formula shown below,

From the formula, we can see a few important points:

- Dependence on Density:

If the satellite is denser (ρs), the ratio (ρp/ρs) decreases, which reduces the Roche limit distance. In other words, denser moons can survive closer to the planet. - Influence of Planet Size and Density:

Larger or denser planets (Rp and ρp) create stronger tidal forces. This pushes the Roche limit outward, meaning looser or less dense satellites must keep a greater distance to remain intact. - Shape and Assumptions:

The given formula assumes a fluid satellite that has no internal strength other than gravity. Real-world objects can deviate from this assumption. A rigid, solid moon, for example, might withstand tidal forces better and thus might survive slightly closer than the simple Roche limit calculation suggests.

TL;DR.

- Tidal Forces: Differences in gravitational pull across a satellite create tidal stresses.

- Roche Limit: A critical boundary where a moon’s self-gravity can’t beat the planet’s tidal pull, causing the moon to disintegrate.

- Application: Explains how rings form from disrupted moons, such as Saturn’s rings.

Leave a comment