I hope this doesn’t “sound” the way it might. Here we are talking about the dynamics of the particular fluid phenomenon which sits at the heart of any propulsion device and it does not mean anything else.

Why even discuss?

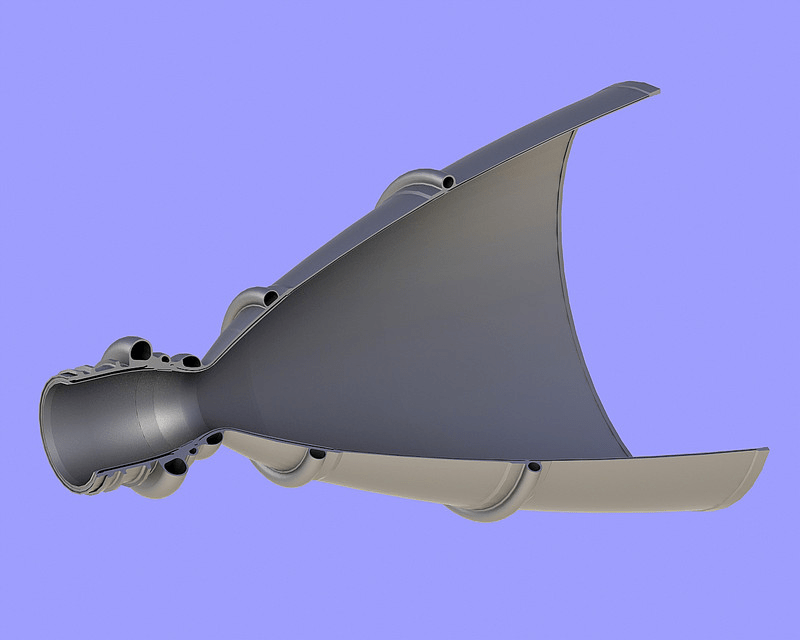

When I first appeared for my interview in the startup I work today as a propulsion engineer, it was a grueling five-day interview. Practically, I didn’t know much about the propulsion industry at that time. The only reason I ended up in the company was because I persisted through all five days. Every day, I used to be around the facility, discussing basic to advanced topics, get questioned at every step, and at night I would read about it. The next day, I would discuss it, fail, then go back again at night, read more, and present again. During those four or five days, one thing that really bothered me was: What the fish is choking in a rocket engine?

I had read about choking, but I didn’t know much about it. For me, choking was just a phenomenon that separated the interior of the chamber from the exterior of the chamber via a converging-diverging nozzle. Also, choking happens at the smallest area of the nozzle (the throat). That was all I knew, and when discussing thruster design, I happen to loosely chose to use this term. That’s when I realized I was doomed because I couldn’t explain it well.

Whatever I have learned since then, I would like to use to explain choking to my past self—someone who was going to appear for an interview—and hopefully, you can also benefit from this process. And why do even discuss it here, well simply, because I own this platform, da! On a serious note, it IS an important phenomenon, so I want my peeps to at least know about it, that’s it!

So what the fish is choking?

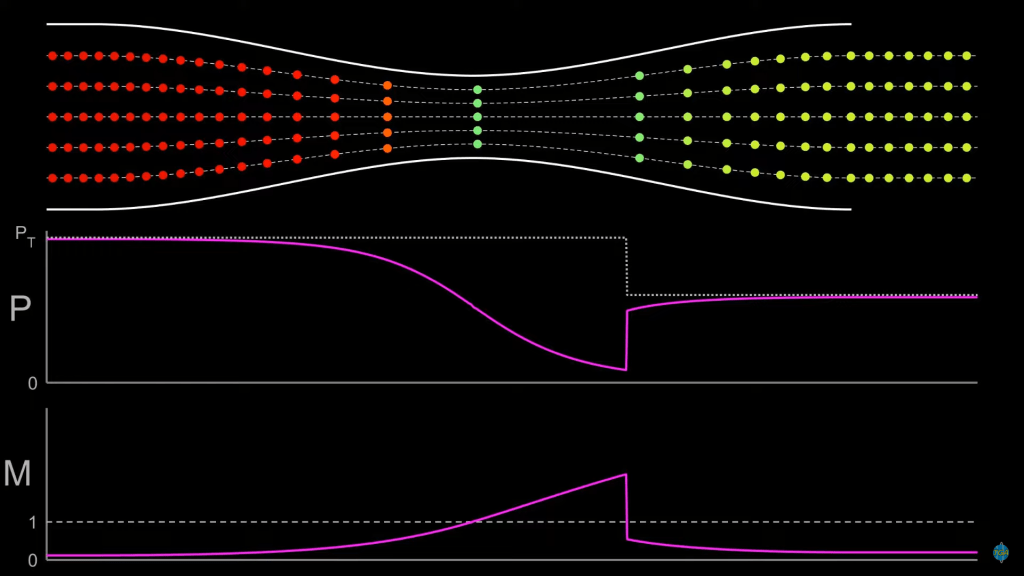

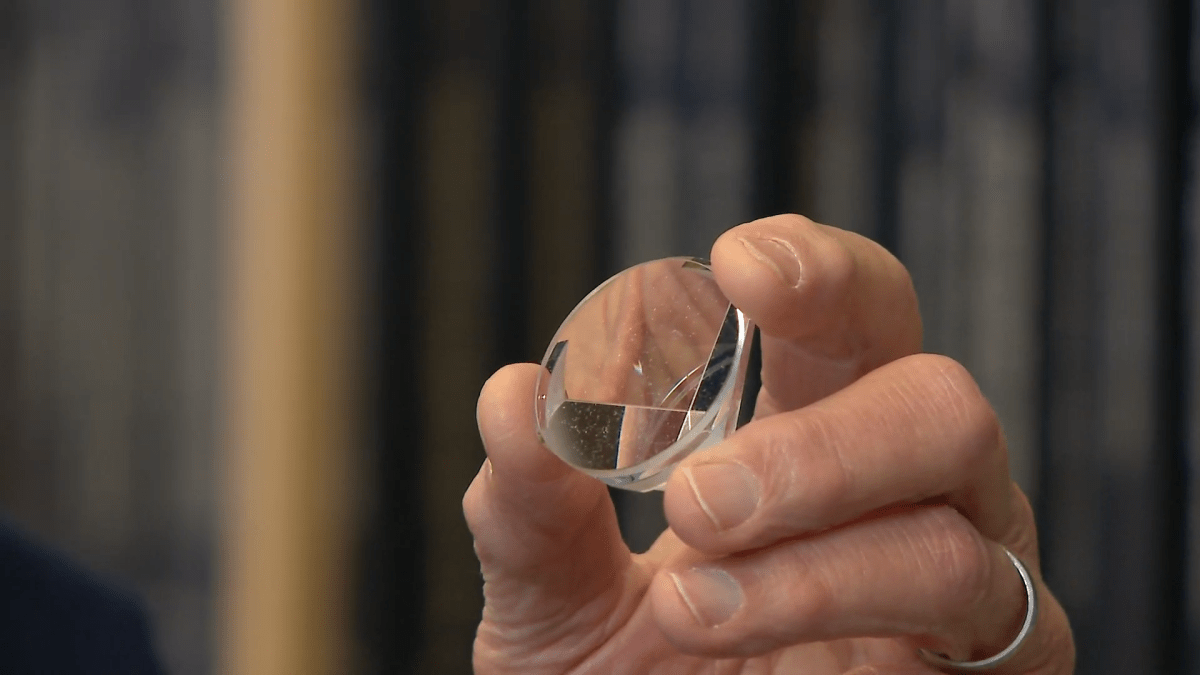

It actually kind of means what it sounds like, but in a more fluid dynamical way. A better way of understanding this would be with a small experiment. Imagine your rocket engine’s combustion end where you have propellants (let’s assume just pressurized air for now). You have a convergent section, a throat, and then a divergent section. In the divergent section, you have attached a vacuum pump whose exit pressure you can vary as needed.

Let’s say initially your exit pressure is equal to the pressure at the combustion chamber. We assume the combustion chamber pressure is constant and that we are only changing the exit pressure.

Case 1: When the exit pressure equals the chamber pressure, NO flow occurs.

Case2: As you decrease the exit pressure, you create a pressure difference (ΔP) across the throat. The pressurized gas from the chamber starts flowing through the throat into the nozzle. Decreasing the exit pressure increases ΔP, which is the driving force across the throat, thereby increasing the mass flow rate through the throat. So far, everything seems fine.

Case 3: However, something interesting happens when we cross a certain pressure ratio. Let’s say the chamber pressure is P, and when the exit pressure goes below about P/2, the mass flow rate doesn’t seem to increase further, even though we are increasing the driving force (ΔP) across the throat. The mass flow rate remains constant. This is what it means: even with a higher ΔP across the throat, the mass flow rate does not increase.

This is what we call choking. In one line: Even if you further increase the driving pressure across the throat by decreasing the exit pressure, beyond a certain point the mass flow rate does not increase. Well that is choking. Why does that happen, what are its implications, how can we achieve it, and what are its benefits? These are topics we are going to discuss in this article.

Do we have “sound” knowledge for choking?

Before we understand why choking occurs, we need to revisit our experiment. We have a rocket engine combustion chamber with high-pressure fluid and a vacuum pump attached to the exit nozzle. We start with the same pressure at both ends. As we reduce the exit pressure, the mass flow rate increases due to the larger ΔP. However, after a certain point, any further reduction in exit pressure does not increase the mass flow rate. This point is called the choke point, and the throat is said to be in a choked condition.

First, we need to understand what happens at the choking point and why it doesn’t react to changes in exterior pressure afterward. Before that, we need to grasp an important concept: How is information even transmitted from one point to another in a fluid medium?

This might seem obvious, but let’s consider a familiar scenario. You are sitting in a room and someone enters. How would you know this without seeing them? By hearing them. The air carries a set of information from the door to your ears, indicating a change—some disturbance, which is in the pressure field inside the room and thus reaching your eardrum. In fluids, pressure waves carry information. Changes in pressure are transmitted by the vibration of air molecules.

What does this even have to do with choking? Well changes in pressure field is the the information itself, the set of instruction! And when we tried to reduce the exit pressure, that information (the reduced pressure) traveled from the exit to the throat and then to the chamber. That’s why the chamber molecules were able to accelerate or adjust to the changing pressure at the exit. By continuously decreasing the exit pressure (thus increasing ΔP), the velocity at the throat kept increasing. The throat is the minimum area, so for subsonic flow, velocity is highest at that point.

As we keep increasing ΔP and thus velocity, there comes a time when the velocity at the throat becomes equal to the speed of sound (sonic speed). At this point, something interesting occurs. Any further reduction in exit pressure tries to pass this information upstream to the combustion chamber. However, the rate at which information (pressure waves) travels is the speed of sound, and now the fluid at the throat is moving at that same speed. This means the information about the lower exit pressure cannot move upstream past the throat. The chamber never “learns” that the exit pressure has been reduced further.

This is the choking point, typically around half the chamber pressure at the exit for air. At this delta P, the velocity at the throat equals the sonic speed, preventing the chamber from reacting to any further decrease in exit pressure. This entire scenario is called choking.

Is choking evil?

Is it bad that our mass flow rate is restricted? Actually, no. It helps maintain stability. It prevents potential instabilities that could occur if the chamber pressure continually adjusted to changes at the exit. By isolating the combustion chamber from these changes, we protect its stability and increase the reliability of the rocket engine. Thus, choking is a very fundamental and important concept in any propulsion device.

So far, we have focused on the throat ONLY, but what about the divergent section? That’s another story. We will explore it another time. Until then, have a “sound” knowledge about choking in rocket engine.

TL;DR.

Generated using AI.

- Choking in a rocket nozzle occurs when flow velocity at the throat reaches the speed of sound.

- At this point, further reducing the nozzle’s exit pressure no longer increases the mass flow rate.

- Pressure changes downstream can’t travel upstream past the sonic boundary, effectively “choking” the flow.

- This stabilizes the combustion chamber conditions and ensures reliable operation of the propulsion system.

Leave a comment