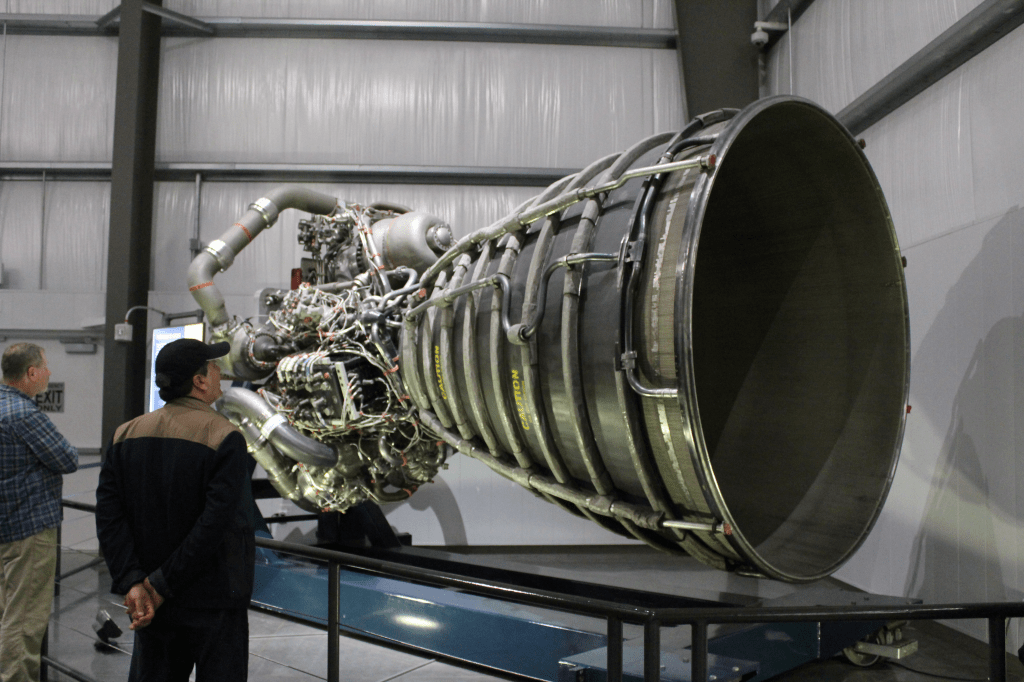

Before I learned about the propulsion mechanics of rocket engines, I often wondered about their operation. I understood that the force exerted by a rocket to propel itself is dependent on the mass flow rate and velocity of the exhaust gases. I also knew that the structure of a rocket engine consists of a combustion chamber, a throat, and then a divergent section. But I always use to wonder about the design of the rocket engine itself!

The quest of achieving higher exhaust velocity.

To achieve higher thrust values, you need to either increase the mass flow rate of the combustion products exiting the rocket engine or increase the exhaust velocity of the same. For the sake of discussion, let’s assume the mass flow rate of the rocket engine is constant, so you would want the exhaust velocity from the combustion to be at its highest speed, right?

In the combustion chamber, the gases accelerate to a certain velocity due to combustion. They then attempt to pass through the nozzle, specifically through the convergent section, where the area for the flow decreases. As a result, to accommodate the total mass flow rate, the velocity must increase, which is clearly observed in the convergent section. Logically, the highest velocity would occur at the throat, the area of minimum diameter. Conversely, if we increase the area of the nozzle to maintain the same mass flow rate, the velocity of the fluid should decrease. Thus, in a rocket nozzle initially increases the velocity of the gas. However, beyond the throat, the divergent section should decreases the velocity, right? We have seen that a decrease in exhaust velocity will reduce the thrust generated by the rocket engine, which raises the question: Why do we even have a divergent section?

The Water Rocket.

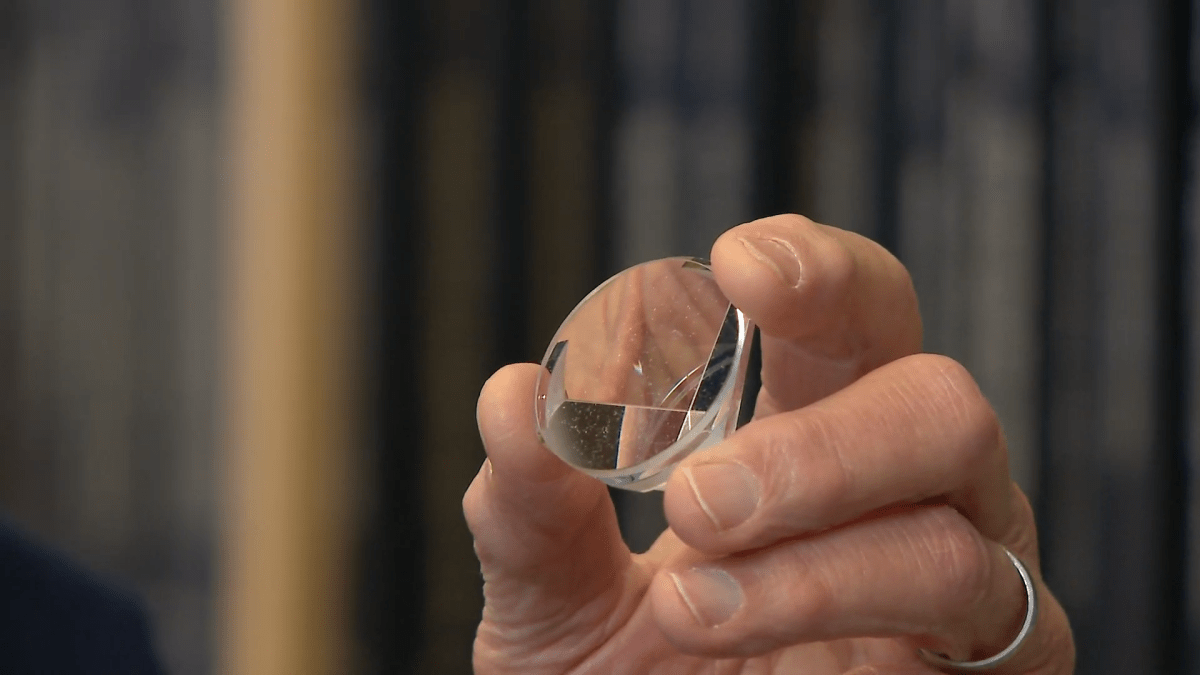

This is exactly what we observe in the case of our water rockets. You have a pressurized medium pushing the water from the bottle to its narrow opening, where as the area decreases, the velocity increases, and the water is ejected from the bottle at its narrowest point to generate the highest possible thrust.

If we increase the area by adding a diverging section, it will decrease the velocity, and consequently, the thrust will not be generated appropriately. Given that our pioneer space engineers are certainly not overlooking this, something different must be happening in the case of rocket engines compared to water jets. What do you think the difference is? Why is having a divergent section essential in one case and detrimental in the case of water?

Chemical Rocket v/s Water Rocket.

The fundamental difference in these two conditions is that in one case, the working fluid is compressible, and in the other, it is incompressible. In the case of a water jet, the working fluid—water—is practically incompressible. What does this mean? The mass flow rate can be described by the equation ρAV, where ρ, the density, remains constant throughout the medium. Thus, the continuity equation simplifies to A1×V1=A2×V2. Therefore, in this scenario, decreasing the area increases the velocity, obviating the need for a divergent section.

However, the situation is not so straightforward in the case of a rocket engine because the working fluid is no longer a liquid, even though the propellants might be. The combustion products are always gaseous and highly compressible. Therefore, the mass flow rate must be written as ρAV, where ρ, the density, can NOT be ignored in this equation. This variable density plays a crucial role in the design of the rocket engine, and we will see later how vital it becomes to have a divergent section.

The Area-Mach Number Relation.

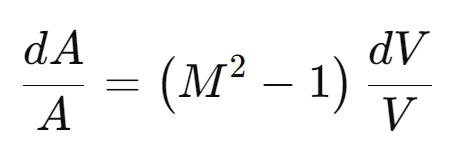

If we analyze the mass continuity, isentropic flow, and thermodynamic properties, we can derive an equation known as the Area-Mach Number relationship. This relationship essentially links the change in the area to the change in velocity, with the Mach number as one of the key parameters. This principle is applicable to both compressible and incompressible flows. But why do we need area-velocity relationship in terms of Mach number? The answer to this question lies in our previous discussion about what exactly ‘choking’ means. Choking occurs at the throat of the rocket engine, where the Mach number reaches unity and the flow speed reaches its sonic speed. The following is the said relationship,

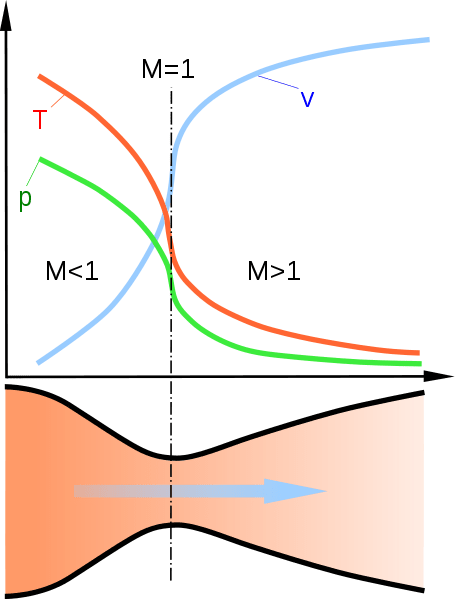

Let us examine the area-Mach number relationship in three scenarios: where the Mach number is less than 1 (subsonic speed), where the Mach number equals 1 (sonic speed), and where the speed is greater than 1 (supersonic speeds).

Subsonic Flow (M < 1): In this case, if the area A increases, the velocity V decreases. Conversely, a decrease in area results in an increase in velocity. This is due to the negative value of (M2−1) when M is less than 1, leading to an inverse relationship between dA and dV.

Sonic Flow (M = 1): At the critical Mach number of 1, any small change in area does not lead to a change in velocity. This is typically where the throat of a rocket nozzle is located (the narrowest part), where choking occurs (flow velocity reaches the speed of sound and mass flow rate is maximized for given conditions).

Supersonic Flow (M > 1): Here, an increase in area A leads to an increase in velocity V. This is because the factor (M2−1) is positive, making dA and dV directly proportional. This is key for the design of rocket nozzles and supersonic rocket engines where expanding the flow area after the throat helps in accelerating the flow further and decreasing static pressure, which is critical for high-speed jets and rockets.

From our previous discussions, we know that at the throat, the flow reaches sonic speed, and immediately beyond the nozzle, it enters supersonic speed. Therefore, if we increase the area after the throat while in the supersonic regime, the velocity continues to increase, which does not occur in subsonic flow. Hence, having a divergent section in a compressible flow, after it has reached supersonic speed, helps in generating higher thrust by increasing the exhaust gas velocity.

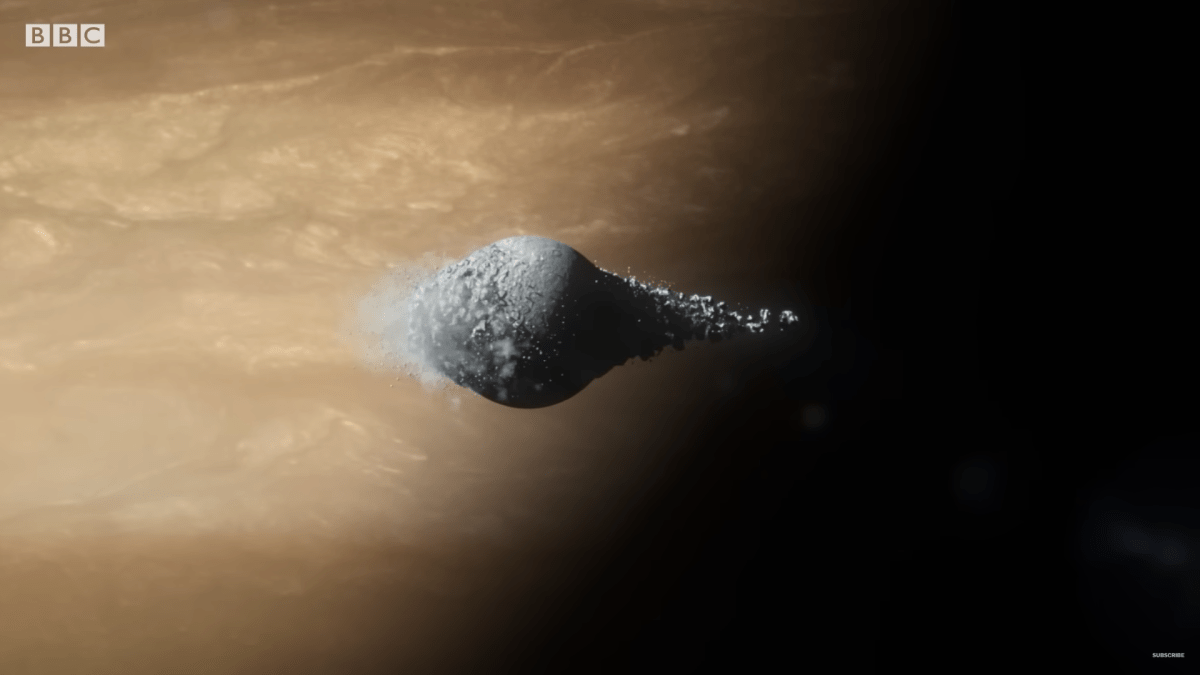

The Cold Fire Condition.

One task to consider is what might happen if the throat of the rocket nozzle is not adequately choked, which could occur with the cold thrust or cold flow of the rocket propellant.

In such a case, if the rocket is designed to operate under hot fire conditions, there’s a possibility that it might not reach choking conditions in a cold flow scenario, even with a gaseous propellant. Logically, we would never reach sonic conditions in this firing mode; all parts of the rocket engine, including the combustion chamber, throat, and nozzle junction, remain in the subsonic regime. Therefore, the velocity will first increase from the chamber to the throat, reaching its maximum at the throat. However, as we continue into the divergent section where the area increases, the velocity must decrease, consequently reducing the thrust generated. Thus, a rocket engine designed for hot fire operation may produce lower thrust when operated in cold conditions due to the dynamics in the divergent section.

What are the basic assumptions we have considered to establish this relationship? We assume that the ideal gas laws are applicable at such temperatures, the flow is compressible, it follows an isentropic process as it passes through the rocket engine.

Path Forward.

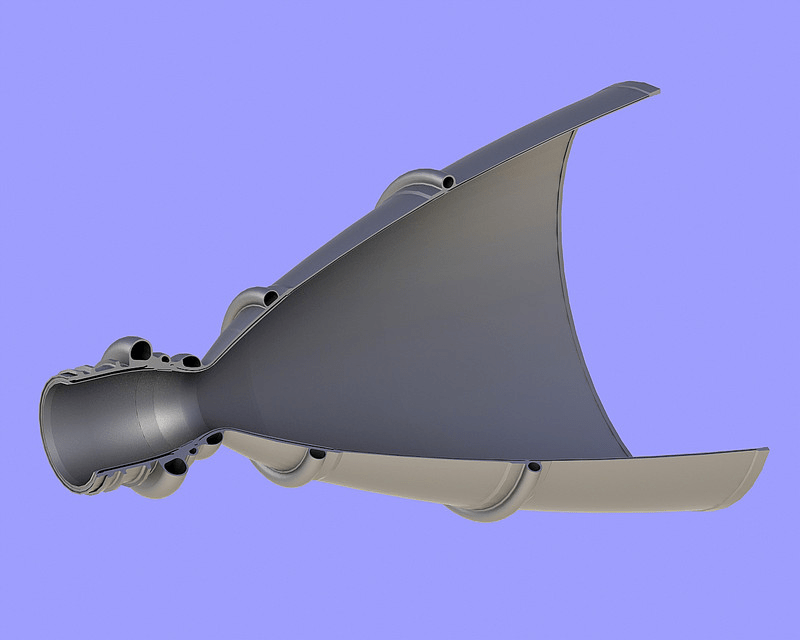

The design of the divergent section is sometimes conical in nature; other times, it is optimized in bell shaped nozzle to achieve the highest possible efficiency. This optimization often involves a value shift, as seen in popular designs that geometrically enhance thrust efficiency. We will discuss these designs in more detail in later articles.

Until then, you now understand why these heavy rocket boosters feature a small combustion chamber, a very narrow throat, and a significantly expansive divergent section.

TL;DR.

- Rocket Engine Basics: Understanding the operation of rocket engines, which rely on mass flow rate and exhaust velocity of gases, structured with a combustion chamber, throat, and divergent section.

- Thrust Optimization: To increase thrust, either increase the mass flow rate or the exhaust velocity; the focus is on maximizing exhaust velocity when mass flow rate is constant.

- Velocity Dynamics: In the combustion chamber, gases accelerate and continue through the convergent section where the area decreases, increasing velocity. The highest velocity occurs at the throat, and adding a divergent section typically decreases velocity, prompting questions about its necessity.

- Water vs. Rocket Engines: Water rockets illustrate how a decreasing area increases velocity and thrust, contrasting with rocket engines where divergent sections play a critical role due to the compressibility of gases.

- Compressibility Factor: Rocket engines use compressible gases, making the density a critical factor in calculations, influencing the need for a divergent section.

- Area-Mach Number Relationship: Describes how area changes affect velocity in subsonic, sonic, and supersonic flows, essential for designing effective rocket nozzles.

- Importance of Divergent Section: In supersonic speeds, increasing the area after the throat increases velocity and thrust, underlining the divergent section’s role in high-performance rocket engines.

- Cold Fire Conditions: Discusses potential performance issues when the rocket nozzle’s throat is not adequately choked, leading to lower thrust in non-ideal conditions.

- Design and Future Articles: The divergent section’s design can vary but is optimized for maximum efficiency; future discussions will further explore nozzle design.

Leave a comment