In a previous article, we explored the need for development of computers and underlying curiosity of the pioneers of industry at that time. Here we dive deep into lives of each of these pioneers and the challanges the faced.

Challenges in Computation

The 1930s marked a period of unprecedented scientific and industrial advancement. However, as fields like engineering, physics, and economics evolved, so did the complexity of the calculations they demanded. Performing large-scale computations was time-consuming and prone to human error. Before electronic computers, scientific calculations were typically conducted using hand-operated methods, such as desk calculators, mechanical adding machines, or laborious punch-card systems. These tools could handle only basic arithmetic and required operators to input data manually and interpret results, which limited their accuracy and efficiency, especially for large data sets.

Manual methods became a bottleneck in research and industry, slowing down critical work in areas such as structural engineering, astronomical calculations, and atomic research. Complex scientific tasks, such as solving systems of differential equations or processing astronomical data, could take months, even years, to complete using manual tools. As demand for rapid, reliable calculations grew, particularly in research settings and during wartime, it became clear that more efficient computational methods were needed.

This environment of technical challenges and limitations created the perfect conditions for innovation. By the mid-1930s, various researchers around the world began to envision a new type of machine—one that could handle calculations autonomously, quickly, and with minimal risk of error. The concept of a machine that could perform tasks traditionally assigned to human “computers” (the term used then for people who performed calculations) was revolutionary, marking the first steps toward automation in computation.

The Pioneering Visionaries of the 1930s

Five independent researchers, each from different disciplines and driven by unique motivations, began exploring the potential of automated computing machines around 1937. Their approaches varied widely, reflecting both the diversity of their backgrounds and the breadth of problems they sought to solve. These visionaries laid the groundwork for modern computing through their groundbreaking ideas and experimental machines, which were radical in their departure from manual and mechanical calculation methods.

- Conrad Zuse (Berlin)

Conrad Zuse, a civil engineering student in Germany, was one of the first to recognize the need for a machine that could perform scientific calculations automatically. Zuse’s studies required extensive stress calculations for structures, which were tedious to perform manually. Frustrated by the slow, error-prone methods available to him, Zuse began to design mechanical aids to assist with these calculations. By 1936, he had developed a design for an early digital computer, known as the Z1. This was a mechanical machine capable of executing basic operations based on a sequence of instructions, making it one of the earliest examples of a programmable device. Zuse’s ideas were visionary for his time. He realized that the key to automation lay in developing a machine that could store and execute instructions independently. His work eventually led to the construction of the Z3, completed in 1941, which is widely regarded as the first fully functional programmable computer. Zuse’s machines introduced several concepts fundamental to computing, including binary arithmetic and floating-point calculation, which allowed his devices to perform complex mathematical tasks with a level of precision that was unprecedented. - Alan Turing (England)

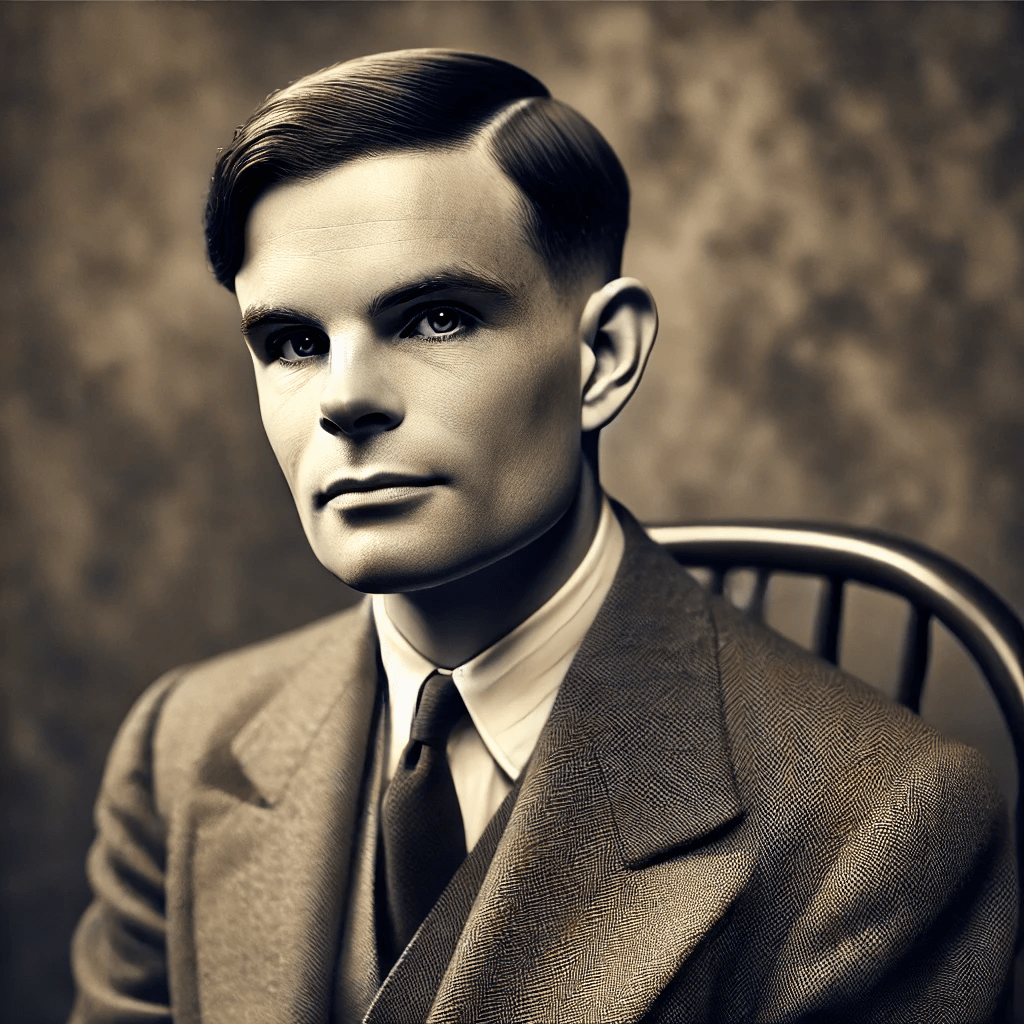

Across the English Channel, mathematician Alan Turing was developing theoretical ideas that would become central to computer science. In 1936, Turing published a paper titled “On Computable Numbers,” which introduced the concept of a “universal computing machine.” His theoretical device, later known as the Turing Machine, could process any computation given the right instructions. While Turing’s machine was purely theoretical, it represented a paradigm shift in thinking about computation, suggesting that a single machine could be designed to solve any problem, provided it could be represented mathematically. Although Turing’s work was not immediately applied to physical machines, it provided a crucial theoretical framework that would guide future developments in digital computing. The concept of a universal machine laid the foundation for programmable computers, inspiring future generations of engineers and scientists to envision devices that could be adapted to multiple purposes rather than being limited to a single, fixed function. - Howard Aiken (Harvard University, USA)

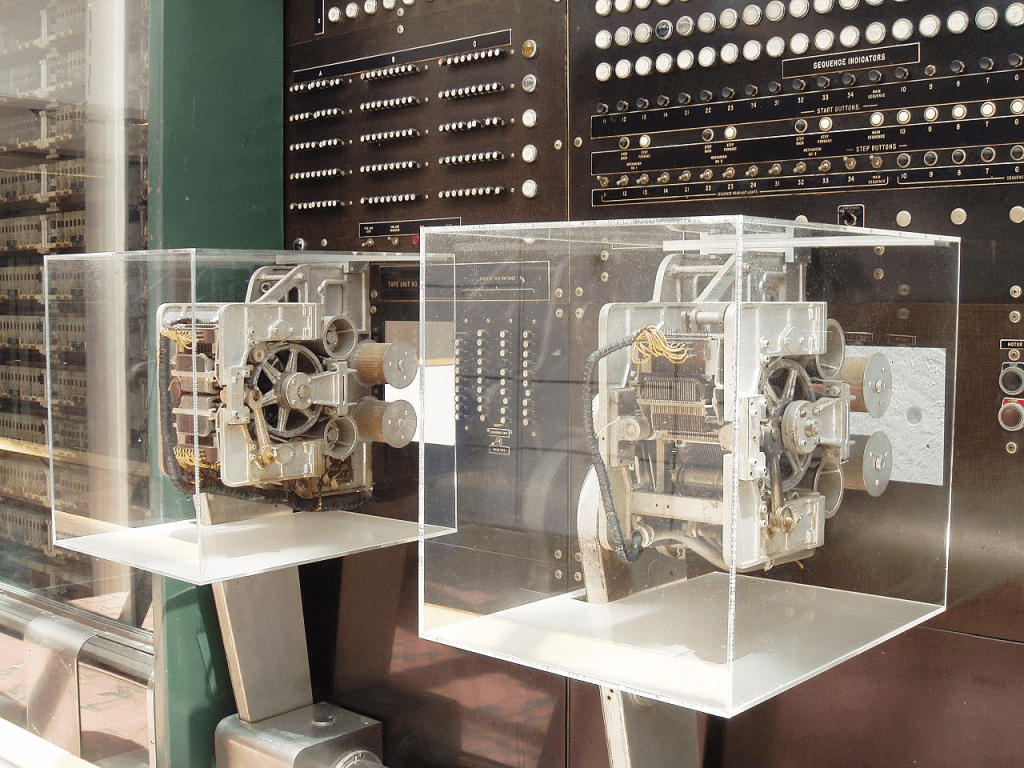

At Harvard University, physicist Howard Aiken was facing his own computational challenges while working on his doctoral dissertation, which involved solving complex differential equations. Inspired by the 19th-century work of Charles Babbage, who had designed but never completed an “analytical engine,” Aiken believed that a mechanical machine could be built to solve non-linear equations automatically. In the late 1930s, Aiken approached IBM with a proposal for constructing a large, electromechanical calculator. His vision led to the development of the Harvard Mark I, completed in 1944, which became one of the first programmable digital computers in the United States. Aiken’s machine, also known as the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator (ASCC), used a system of relays and mechanical components to perform calculations and could be programmed using punched paper tape. The Mark I was capable of handling large-scale calculations and became an invaluable tool for the U.S. Navy during World War II. Aiken’s collaboration with IBM marked the beginning of the computer industry in the United States, as IBM engineers contributed their expertise in punched card systems and relay technology to help build the Mark I. - John Atanasoff (Iowa State University, USA)

In Iowa, physicist John Atanasoff was focused on a specific computational challenge: solving systems of simultaneous linear equations. Recognizing the limitations of mechanical calculators, he began developing a machine that would rely on electrical components instead of mechanical parts. Along with his research assistant Clifford Berry, Atanasoff built the Atanasoff-Berry Computer (ABC), which became the first device to incorporate binary arithmetic, electronic switching, and capacitor memory. The ABC, completed in 1942, was designed to solve equations quickly and accurately, making it a precursor to modern digital computers. Atanasoff’s work introduced several critical concepts, including the separation of memory and processing functions, and the use of binary arithmetic to simplify computations. Although the ABC was not a programmable machine, its design influenced later developments in digital computing and helped establish the feasibility of electronic components in computing machinery. - George Stibitz (Bell Labs, USA)

In the late 1930s, George Stibitz, an engineer at Bell Laboratories, began experimenting with relay circuits—a technology commonly used in telephone switching systems. Stibitz noticed that relays could represent binary states (on and off), inspiring him to explore the possibility of using binary arithmetic in calculation machines. His work led to the construction of the Complex Number Calculator, one of the earliest relay-based computers capable of performing arithmetic on complex numbers. Stibitz’s work at Bell Labs demonstrated that binary arithmetic could be used in practical, real-time computation, proving the feasibility of relay circuits for digital logic. In 1940, he conducted a landmark demonstration where the Complex Number Calculator was remotely operated from hundreds of miles away via a telephone line, making it one of the earliest instances of remote computing.

The Independent Nature of Early Research

Each of these pioneers worked independently, often without knowledge of the others’ developments. Communication between scientists was limited, and the field of computing had yet to become an organized discipline. Each of these individuals was driven by a unique set of motivations and challenges, from solving academic problems to addressing wartime needs. Despite their isolation, their work collectively laid down essential principles of computing, including binary arithmetic, automated calculation, programmable logic, and memory storage.

The Birth of New Principles and Technologies

The work of these pioneers introduced revolutionary ideas that would become the foundation of modern computing. Binary arithmetic, for instance, simplified complex calculations by reducing operations to sequences of 1s and 0s, making them easier to implement in electronic circuits. Relay circuits and, later, electronic switches provided a means to perform logical operations quickly and reliably. Programmable logic allowed computers to follow complex sets of instructions, a fundamental capability that transformed machines from simple calculators into versatile problem-solving tools. By the end of the 1930s, these separate efforts had collectively established a new approach to computation—one based on the idea that machines could automate logical operations and perform calculations far more quickly and accurately than humans. This marked the beginning of the digital revolution, setting the stage for the rapid advancements of the 1940s and beyond.

A Legacy of Innovation and Inspiration

The contributions of these pioneers were not merely technical but also deeply inspirational. They challenged the status quo and demonstrated that even the most complex problems could be solved through innovation and a willingness to experiment. Their work inspired subsequent generations of computer scientists and engineers to push the boundaries of what machines could achieve. The ideas developed in the 1930s were further refined and expanded during the 1940s, eventually leading to the development of fully electronic, programmable computers in the 1950s. Today, their legacy is evident in every digital device, from smartphones to supercomputers, as their foundational concepts continue to underpin modern computing technology.

Leave a comment